Introduction

I’ve heard it claimed over the years that one of the main trends in higher education is to increase the number of adjunct and short-term faculty and decrease the number of tenure-track faculty. I wondered if it would be possible to see evidence of this trend based on philosophy job ads found on PhilJobs.org. Using some quick pivot tables and visualizations in Excel, I was able to determine that the this does indeed seem to be a trend in philosophy hiring. However, the trend is not as severe or radical as I expected. Unfortunately, the quality of the analysis is limited by the fact that many adjunct or short-term (e.g., per course or per semester) job postings don’t appear on PhilJobs, but still, I think the analysis confirms what seems to be a trend in higher education overall.

Background

Anecdotally, I’ve heard time and again from friends and colleagues in higher education that the institution of tenure for academic faculty members is being eroded. Based on two reliable sources. I think this claim is true. The first is a Government Accountability Office report from 2017 found that some “70 percent of postsecondary instructorial positions nationwide” are contingent faculty outside the institution of tenure. (You can read the IHE writeup on the report here.) Perhaps the most striking chart comes from p. 9 of the report, which shows that while full-time and part-time contingent instructional positions increased by over 100% each in the period between 1995 and 2011, in the same period, full-time tenure-track positions only increased by 9.6%. (Full disclosure: I don’t understand how the percent changes are calculated here. The value I get seems to be 1/2 of the ones stated in the report.) The second source is a 2018 analysis by the American Association of University Professors based on 2016 data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System and similarly found that 73% of all instructional faculty were not tenure track, further confirming this trend. Given how well-supported this trend seems to be, I was curious if we could find evidence of it by looking at philosophy job postings over the past decade, from 2014-2023, based on philosophy job posting data.

Getting the data

My main data source for this analysis is PhilJobs.org, which aggregates job ads in philosophy from around the world. It doesn’t contain every single job posting in philosophy higher education by any means, but it is a widely-used site in the field and, most importantly, allows visitors to download multiple job postings as a csv file.

On 28 November, 2023 I did a search with no parameters that included expired ads and downloaded a file that included as many ads as the system would allow, totalling in 6510 going back all the way to August 2013. The website shows listings going back to 2011, but the csv file only goes back as far as August 2013. (Presumably I could write a data scraper with Python to do it, but for now I’ve just settled for using data going back as far as 2014, since that’s the first full year of job data I have.)

The data are pretty intuitively organized and not in need of much cleaning (at least for this analysis), since the things I’m interested in are all Nominal and Categorical data, so all the job postings have the contract type and job type in distinct nominal categories. Once I had the file, I simplified the spreadsheet to include the ID number, job type, and contract type. The job type and contract type are the most interesting to me for now.

My next step was to make a pivot table that determined the number of observations per year of each variable under job type and contract type. In particular, I was interested in the number of each job and contract type as well as that number as a percentage of the total number of job ads for that year. The reason for adding the percentage is because I figured it would be easiest to track the trends of one job type versus another more easily than if I used the raw number, since the number of job ads on the website could fluctuate each year. (However, the number of job ads per year was remarkably stable, so the percentage was actually less useful than I imagined. More on that later.)

Analysis

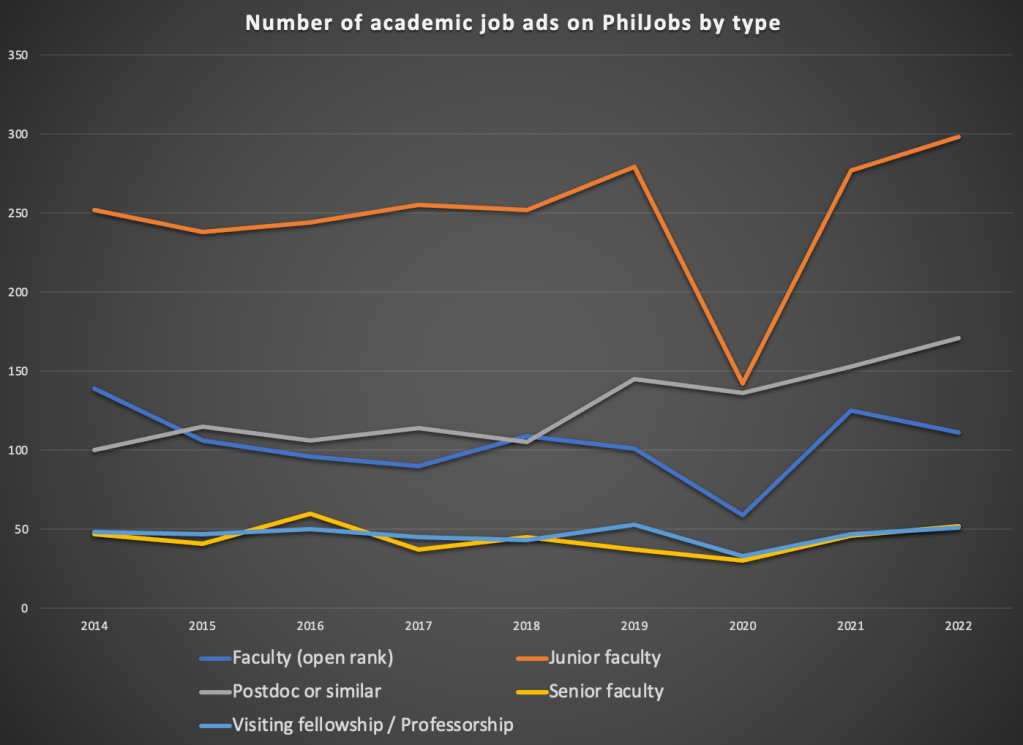

With the pivot tables made, I could then generate some visualisations of the data, and perform some analyses, regarding trends in the type of jobs ads posted on PhilJobs over the past decade. I started by visualizing the raw number of job ads for the three biggest academic job categories: Open rank, junior faculty, and postdoc or similar. (I omitted senior faculty, graduate fellowship, and nonacademic jobs from the analysis since they made up a rather low percentage of all the job ads posted.)

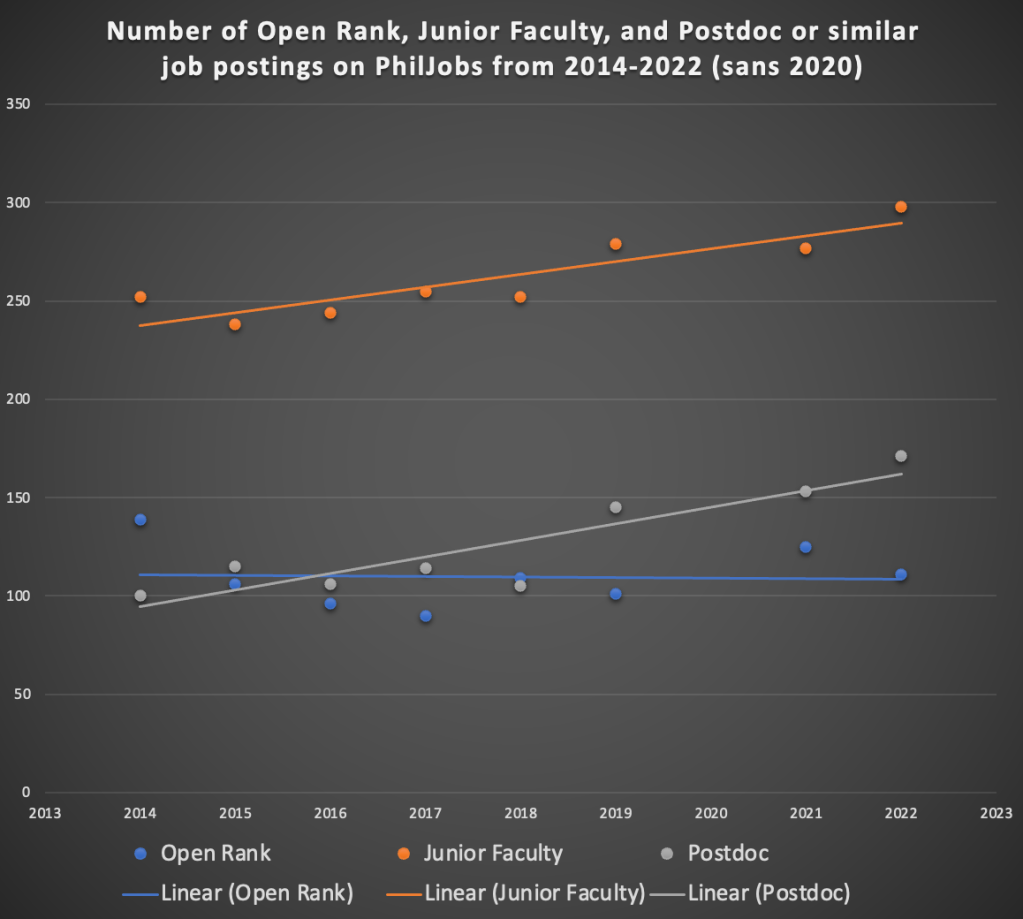

The number of open rank, junior faculty, and postdoc or similar job ads on PhilJobs for 2014-2022 looks like the following:

We can observe a few things. First, the number of junior faculty positions crashed during 2020, no doubt due to the pandemic. Fortunately, the number of ads seems to have largely recovered in this category, but not nearly enough to offset the gross number of job ads lost by the 2020 crash, since the number of jobs in 2021 and 2022 look more like a regression back to the mean than a correction for the 2020 crash. In other words, it still looks like around 100 junior faculty job ads are missing because of the pandemic. The results for 2023 remain to be seen, but currently (with 269 junior faculty jobs posted as of 28 November) it doesn’t seem like an equal and opposite correction from the 2020 crash is in the cards. Those jobs may be gone for good.

The number of open rank jobs dipped that year as well, but not nearly as much as junior faculty ads. Open rank ads also seem to to have bounced back more robustly in 2021 than junior faculty ads. Surprisingly, the number of postdoc or similar ads barely moved at all during 2020. The number of senior faculty and visiting fellowship/professorship job postings has also been remarkably stable, as does the number of open rank positions.

In terms of the trends, postdoc and junior faculty jobs do appear to be trending upwards, but not by a substantial amount. Open rank positions also seem to be trending downward, but it’s too difficult to tell without a linear regression. Senior faculty and visiting fellowships seem too stable to bother with—the trend there seems negligible, whatever it may be.

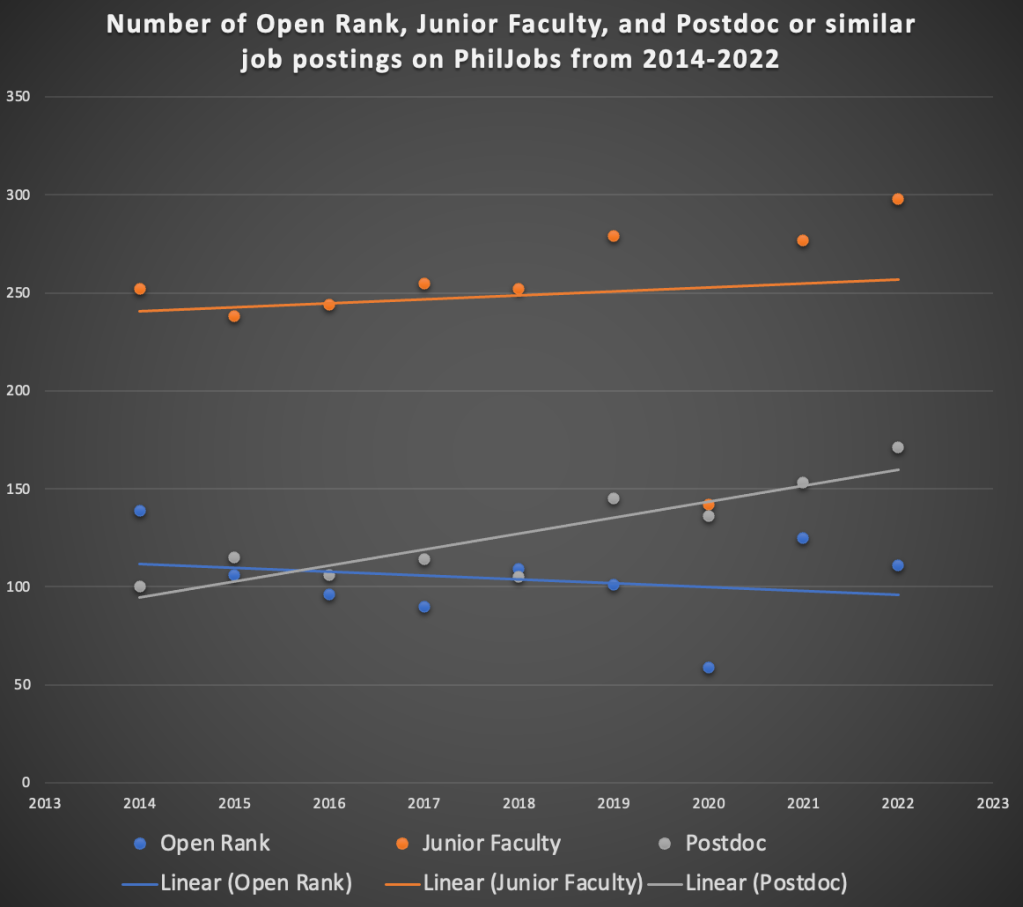

Upon converting the chart to a scatter plot and adding a trendline, we can see that the number of junior faculty ads and postdoc ads on the PhilJobs has been increasing each year, while the number of open rank positions has been decreasing. The slope of the linear regression for junior faculty positions was 2.01, which we can understand as the average number of jobs per year added for that category, while that of postdoc or similar positions was 8.15, meaning that the rate of increase for postdoc ads was four times greater than that of junior faculty ads.

One tricky thing to note though is that the pandemic had a far greater impact on the number of junior faculty jobs than it did on the number of postdoc jobs. It also had a substantial impact on open rank jobs.

To correct for this, I removed the 2020 data from the chart and trendline calculation. As a result, the slopes of the linear regressions for junior faculty and postdoc jobs are much closer, with a value of 6 and 8.45 respectively, meaning that for every 6 junior faculty jobs ads that were posted on average, 8.45 postdoc ads were posted. Of course, this might overcorrect in the opposite direction, since a percentage of those job ads in 2021 and 2022 might be making up for some of the ads not posted in 2020, so in a couple of years, the trend may eventually look more like the original chart that includes 2020. It will be interesting to see what 2023 brings.

Both charts suggest that postdoc ads and junior faculty ads are both increasing, though the rate at which postdocs ads are increasing is definitely higher than that of junior faculty ads.

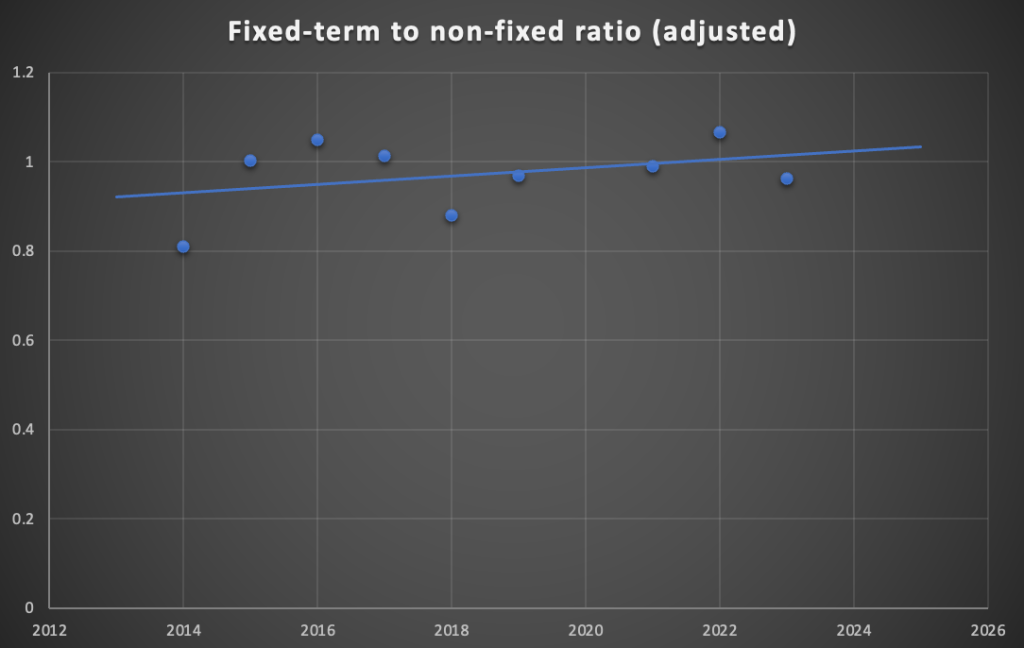

A second thing I wanted to check was the contract type for each job ad, the hypothesis being that the ratio of fixed-term to open-ended, tenured, or tenure-track contracts should be increasing as time goes on. Fixed-term contract jobs typically include visiting professor positions as well as postdoc contracts. To determine this, I simply calculated the ratio of fixed term contract ads to open-ended/tenured/tenure track contract ads. The following scatter plot plus linear regression shows a noticeable increase in the ratio, confirming the hypothesis.

However, there’s an obvious problem: the spike in the ratio in 2020 skewed the slope of the regression upward. If we remove the data from 2020, treating it as an outlier, the increase in the ratio is far more modest, but definitely present. Interestingly, it looks like 2019 was the year that advertisements for fixed-term contracts overtook those of non-fixed-term contracts on average. So far, 2023 still has more non-fixed-term contracts than fixed-term ones, but the year isn’t over yet, so it’s still possible for this to change in the next month or so. (I will definitely make an update after 2024 to this effect to see if the total number of fixed term job overtook the total number of non-fixed-term ones.)

Based on the revised trendline, I think it’s fairly safe to assume that the ratio of fixed term to non-fixed term positions posted on PhilJobs will continue to increase as time goes on.

Some caveats

Some caveats are in order so as to not read too much into this analysis:

- Many adjunct positions are not advertised on PhilJobs. (In fact, a convenience sample of philosophy adjunct opportunities in New Jersey from last year did not find any corresponding advertisements on PhilJobs.) I suspect this data qualifies as “Missing Not at Random”, since the fact that the jobs are short-term is the reason why they are not posted on PhilJobs.

- Sometimes the contract types and job types do not precisely correlate. For example, a lecturer job might have a tenure-track equivalent contract structure, but is advertised as a fixed-term position.

- The contract-type ratio was performed including non-academic, RA, and graduate assistant jobs as well, and it’s unclear if that subset skews towards a certain type of contract. However, there are so few jobs in that category and any trends associated with those categories seems negligible. A more accurate analysis for academic jobs would exclude these kinds of jobs.

Conclusion

The claim that instructorial jobs in higher education are increasingly going to fixed-term and non-tenured faculty seems to be confirmed by an analysis of the job advertisements in philosophy higher education posted on PhilJobs. The short analysis here found that:

- The number of postdoc or similar ads on PhilJobs is increasing at a higher rate than that of junior faculty ads.

- A nonnegligible number of junior faculty ads are missing from 2020 due to the pandemic. Subsequent years have not yet corrected for them.

- The overall number of open-rank positions in philosophy is trending downwards, but not by very much.

- The ratio of fixed-term to non-fixed-term contracts is increasing.

The biggest wildcard is the amount of adjunct jobs in philosophy not posted on PhilJobs, which for all I know could have exploded over the past 10 years. Based on the PhilJobs data, however, the trend towards hiring faculty on fixed-term contracts is clear, but not as dramatic as I expected.

Leave a comment